If you stand at the original entrance to the Bridgewater College campus—at the crossroads of Broad and Third streets—and look toward the campus mall, the view in front of you looks much like it did decades ago. But as you begin to walk toward Rebecca Hall, a dramatically different view begins to emerge. By the time you make your way to the two-story glass tower entrance to the John Kenny Forrer Learning Commons, it’s clear that the more than five-decades-old Alexander Mack Memorial Library has been transformed into something extraordinary.

The façade has been altered to incorporate panoramic windows with vistas of campus, and the interior has received a transformational upgrade. The primary purpose of the building—to support and enhance learning—remains intact, but the way in which the College accomplishes that goal has changed dramatically.

In 1961, the College sought philanthropic investments to construct a modern library that would further academic instruction and allow for flexibility in use. The Board of Trustees was open to naming the new facility for any donor who contributed a substantial portion of the construction cost. Absent that, the board would name the building as a tribute to Alexander Mack Sr., founder of the Church of the Brethren.

Although the Mack Library, as it became affectionately known, served the needs of students and faculty for many years, changes in technology and the evolution of students’ learning styles meant an update was essential to continue to foster student success. In fact, the magnitude of those changes in learning demanded that any update take the form of a thorough reimagination, inside and out.

A library renovation was added to the College’s 2020 Strategic Plan, and in 2014 President David Bushman tasked a Library Study Committee with drafting a proposal for a modern library that served the core mission of the College and acted as a centerpiece for the academic community.

“We’re not breaking with our past,” says study committee co-chair and John Kenny Forrer Learning Commons Director Andrew Pearson. “We’re continuing that vision and moving into the next century.”

Just as the physical building bridges the College’s past with the present, so too does Bridgewater’s continued focus on student success. The Forrer Learning Commons embraces that goal by combining academic and technology resources, tutoring and more into one space.

“The Mack Library served as this solid foundation upon which the institution could build,” says Dr. Maureen Silva, Vice President of Institutional Advancement. “It served as that initial spark, and it continues to light the way.”

ESTABLISHING A VISION

A shift had emerged in academic libraries during the last 10 years. Research and study needs remained, but students were starting to work differently. They were completing project-based assignments and becoming more collaborative. They were increasing their use of technology. Libraries (both academic and public) were viewed as community hubs where the exchange of ideas and meetings took place.

“The vision to transform the library was based on the realization that the nature of an academic library had shifted from a place where you go solely to find information into a place where you go to create something with that information,” President Bushman says.

In March 2014, Pearson, study committee co-chair and Director of Information Technology (IT) Kristy Rhea, and architectural consultant Raymond Hunt attended the Academic Library Planning and Revitalization Institute in Denver. There they were introduced to best practices at other academic libraries, including the University of Denver’s recently renovated library, now called the Anderson Academic Commons. A few themes emerged: A successful facility includes a variety of study areas to support different learning modes, and an increase in light and sight lines invigorates a facility with new energy that inspires different forms of study, research and social engagement.

“We wanted to engage a design that would meet the rhythm of our students,” Pearson says. “We didn’t just want to create a location with furniture; we wanted to create an experience.”

During the planning phase, it was determined the Mack Library was located in the perfect place. Drone shots taken from overhead illustrated how the building was situated at the crossroads of campus. And the location had a natural energy about it: “The library’s presence during the day is magnified at night by its illumination of the campus mall. It radiates the energy and activity of a learning community that educates the whole person,” states an excerpt from the Lighting the Way for the Next Generation Library Study Committee report.

The goal then became for the committee to draw a road map for the needs of the Bridgewater College community. Because the library brings together so many different constituencies, the committee consisted of 19 members from several stakeholders on campus: the library, IT, Student Life, Admissions, the Office of Institutional Advancement, the Finance Office, Academic Affairs, the Writing Center, faculty and students. The committee took inventory of how the current library functioned, as well as conducted close to 70 interviews with representatives from every program on campus. Committee members collected feedback on not only how programs interacted with and used library services but what their ideal exchange would look like. Several recurring ideas emerged during the interview process: “community,” “open,” “flexible space,” “meeting space,” “information hub,” “cross-discipline study” and “student service and support.”

And program directors weren’t the only group surveyed. With student success as the main focus, the committee designed a survey to gain input from students on furniture and seating, the environment, amenities and services. Tables or group study rooms were preferred over single chairs and carrels. The need for food, drink and café space was highlighted. And students said they would be more likely to use services such as the Writing Center, IT HelpDesk, Academic Advising and Academic Support if they were all located in one central location. The need to create a one-stop shop for students where they could engage with each other and find additional resources outside of the classroom was clear.

“We were tasked with thinking outside the box and not thinking about a traditional library,” Rhea says. “It was about what the College needed and what a building could do to bring services together to propel the academic side of the house.”

THROUGH THE YEARS

1883 – Bridgewater College’s predecessor, the Virginia Normal School, consisted of one school building, which held a library on its first floor from 1883-1889. It’s uncertain if or how many of the College’s books survived the fire of 1889, which destroyed the building once standing on the site of Flory Hall.

1890 – College Hall, now known as Memorial Hall, was constructed to replace the former main building. The library moved to College Hall in 1890, staying there until 1904. The library was located in what is today the first room to the left of the entrance.

1904 – The growing library was moved to the ground floor of the newly completed Founders’ Hall (today the Registrar’s Office in Flory Hall). Bridgewater’s collection of books expanded rapidly to 10,000 by 1910.

1929 – The library moved to the basement of Cole Hall, following the building’s completion that same year. The new home contained enough shelf space to hold approximately 30,000 volumes.

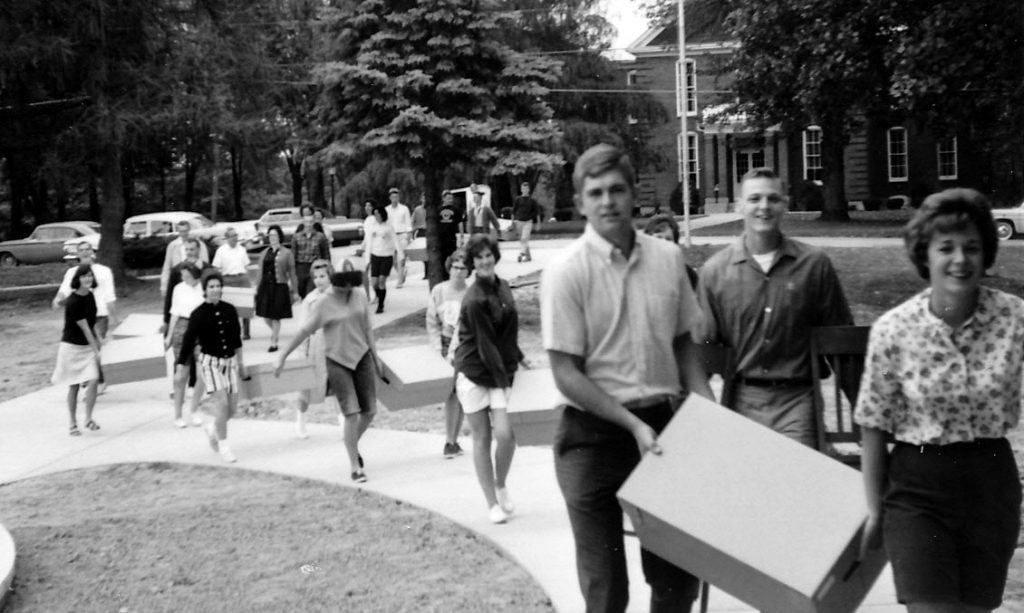

1963 – By the mid-20th century, the library’s collection had grown to 50,000 volumes and books were stored across campus. The BC Board of Trustees approved plans for a new library, and the Alexander Mack Memorial Library was completed in 1963. On Sept. 18, 1963, students volunteered to participate in Operation Booklift, during which they moved 50,000 books to their new home in just four hours and nine minutes.

The only campus building ever constructed for the sole purpose of serving as a campus library, Mack Library boasted 32,689 square feet of space, shelving for approximately 115,000 volumes and seating for 275 students. The College’s special collections, including research and archives space, was allotted 1,200 square feet. In addition to its own impressive collection of manuscripts and rare books, Mack Library’s vault and Brethren Room housed records for the Reuel B. Pritchett Museum, the town of Bridgewater and regional Church of the Brethren congregations. The library was also a government documents repository.

*Timeline information collected by Chris Conte ’14 and Special Collections Librarian Stephanie Gardner for the Bridgewater College Special Collections exhibition commemorating the Alexander Mack Memorial Library’s 50th anniversary in 2013.

The committee’s final report, presented to President Bushman, identified 24 types of spaces for consideration within the renovation. The report findings allowed the Quinn Evans architect team to start at “the 50-yard line,” says Pearson.

“What was really helpful and really smart was there was a group of folks that were brought to the project committee that had different perspectives that were complementary in the context of one another that informed the design holistically,” says Chuck Wray, lead project architect with Quinn Evans. “It was nice to see that kind of spirit about this building because it really was true to the mission that was established. You could tell there was tremendous buy-in across campus and that this could possibly be one of the most transformative things that happens on campus for a long time.”

Study committee representatives and the architectural team visited other colleges and universities to take note of design ideas and hear best practices. Some of those elements are woven into the finished product, such as the study pods in the Great Room and the expansive fireplace adjacent to the café.

Quinn Evans also led a second student survey on furniture preference. The College administration then had furniture samples delivered to the Mack Library so that students could try out each piece and share what they liked best. Rhea says the input was key in that students demonstrated not just what they preferred but how they would use each piece. Meeting students’ needs was a priority.

“In that respect, the space is more personal to the students because they had the ability to provide feedback on what resonated with them,” says Quinn Evans interior designer Shannon Wray.

WITNESSING THE TRANSFORMATION

The College broke ground on the John Kenny Forrer Learning Commons project in May 2018. The construction, which added 10,000 square feet of space, took under two years, and the building opened on Feb. 24, 2020.

“Before, you had a library from the ’60s that could have been on any campus,” Shannon Wray says. “What you have now is unique and specific to Bridgewater. It doesn’t exist anywhere else.”

Two of the most dramatic and distinctive aspects of the physical transformation are the glass Clinton E. De Busk Tower entrance and the cantilevered great room that provides expansive views of the campus mall. Bringing the outside in, and adding as much natural light as possible, was integral to the design, according to the Wrays.

“The building architecture responded to the campus,” Shannon Wray says. “Whereas the previous library was insular, this one is much more transparent and outwardly focused. We said, ‘How can we make this glow and be a beacon on campus?’.”

When looking at the blank floorplans, Chuck Wray says the shell of the building looks similar to the Mack Library with its modular layout. But one look around the renovated Forrer Learning Commons proves the College’s vision to create a modern, engaged academic learning hub was realized.

The split-plan first floor draws visitors up the stairs and to the concierge desk in the Morgridge Center for Collaborative Learning. Here, visitors can inquire about books from the 90,000-volume Alexander Mack Memorial Collection, as well as connect with technology support from IT and the Digital Scholarship Gurus, the Writing Center, peer coaching, tutoring and research support, and practice presentation and audio recording rooms. Career Services also has an office space that is integrated with the learning support programs, underscoring the importance of focusing students on their careers throughout their four years on campus.

On the first and second floors, quiet study areas are complemented by group meeting spaces and engaged learning classrooms—many of which were named by donors who invested in the project. The modern furniture is flexible and movable by design, so that students can tailor the space to their needs. Interactive walls that can be drawn on provide new opportunities for study techniques, and digital assets such as large screens and power outlets near every study space ensure that students can embrace 21st-century learning modalities. The Alexander Mack name remains prominent in the new Forrer Learning Commons in the form of BC’s entire collection of bound volumes, with the majority of the Alexander Mack Memorial Collection housed in compact shelving on the lower level adjacent to the College’s archives and special collections—a move that opens up flexible learning space on other floors.

Additionally, the art gallery, portico, great room and Smitty’s Café offer a variety of opportunities for engagement and enrichment. Outdoor seating spaces allow the activity of the Forrer Learning Commons to spill outside, where students and faculty can read, dine and interact with one another.

NAMED SPACES

Bridgewater College is eternally grateful to every donor who contributed to this truly transformational project. The following are current named spaces at the John Kenny Forrer Learning Commons:

The building

- John Kenny Forrer Learning Commons

- Clinton E. De Busk Tower

- Alexander Mack Memorial Collections

Main floor

- Morgridge Center for Collaborative Learning

- Smith Family Café (Smitty’s)

- Robert H. ’59 and Mary Susan King Portico

- Beverly Perdue ’68 Art Gallery

- Dr. Kenneth ’63 & Nancy Bowman Academic Resource Suite

- David T. Christian ’06 & Caitlin R. Christian ’07 Staircase

- Stuart R. ’63 & Lorraine C. Suter Learning and Research Services Suite

- Wilkerson Family Practice Presentation and Audio Recording Room

- Mark A. Sherman ’92 Fireplace

- Andrews Family Café Seating

- D. Cory Adamson ’91 Café Seating

Upper level

- The Class of 1969 Great Room

- The Mary Morton Parsons Foundation Study Area

- Fred O. Funkhouser Instruction Room

- L. Daniel ’50 and Louise ’54 Roller Burtner Family Instruction Room

- Edgar ’58 & Kathy ’60 Simmons Director’s Office

- Frank ’81 & Aida Roa Great Room Seating

- Thompson Family Foundation Instruction Room Technology

- Paul P. ’63 & Martha A. Vames Family Study Room

- D. Cory Adamson ’91 Study Room

- The “Reiding” Room

- Shively Family Study Room

- Wil ’63 & Joyce Nolen Study Room

- Donna Price Walker ’75 Study Room

- Carolyn Hupman Beach ’69 Study Room

- Hope Harman Hickman ’78 Study Room

Lower level

- Robert R. Newlen ’75 & John C. Bradford Special Collections

- Janice W. & Ronald E. Sink Family Brethren Room

- Kloster Family Study Area

- Benjamin ’82 & Sherrie ’85 Wampler Archival Reading Room

Exterior

Wampler Family Plaza

Alison’s Reading Terrace

The opportunity for connection, though, extends to the program partners now housed under one roof. Pearson has organized regular meetings with all Forrer Learning Commons partners to brainstorm ways for increased collaboration.

“Co-locating the student support functions with academic library functions results in improved retention from freshman to sophomore years,” Chuck Wray says. “Bridgewater really got it. They understood the value in co-locating them and showcasing it. I think it pays dividends for decades to come.”

Sherry Talbott, Director of Career Services, which is now housed in the Academic Resource Suite along with the Writing Center and academic tutoring, has already started collaborating with the neighboring Writing Center to provide workshops for writing tutors so they can better understand how to aid their peers with resumes, cover letters and personal statements. She believes that being located in a more highly visible area creates more opportunities for students to connect with Career Services and other resources while allowing for more organic, creative collaboration across the board.

“Our vision was a symbiotic energy of these different services collaborating in such a way that they exceed the sum of their parts,” Pearson says. “The things you are doing together here are something you could never accomplish by yourself.”

On opening day, students, faculty and staff streamed in the front doors to witness the library’s transformation. The students immediately settled into individual study spaces, gathered together in group study rooms and spent the day enjoying their new connectivity hub.

President Bushman walked over to the Forrer Learning Commons the next night to show the building to a friend. At 9:30 p.m. he estimates 500 to 600 students—a third of the campus—were in the building, using it exactly how the administration and design team imagined it.

“It was really gratifying to see that,” he says. “This building exceeded expectations in every way imaginable.”

Although the College was forced to shift to remote learning a few weeks after the Forrer Learning Commons opened due to COVID-19, the Learning Commons remained a resource for students in the 2020-21 academic year when they returned to campus. Samantha Hince ’22 covered opening day for the student news organization BCVoice. She says every student she spoke with had positive reactions and that there was a palpable excitement as they explored the space. Hince completed an internship last year with the Office of Career Services and says she spent so much time in the Learning Commons she and her friends jokingly referred to one of the study rooms as her personal office.

“I think the biggest benefit that the Learning Commons offers students is a flexible work space,” she says. “Between group study rooms, personal study desks and individual reading nooks, there’s a space for any type of work you need to do. I also think it’s wonderful there are so many great resources easily accessible to students.”

DIGITAL SCHOLARSHIP GURUS: HELP FOR A DIGITAL AGE

By Olivia Shifflett

The Writing Center and Math Center continue to regularly assist students in their studies, but as technology use has grown, a new kind of support service need at BC emerged. Enter the Digital Scholarship Gurus—students who assist other students, as well as faculty and staff, in a variety of digital projects. Since the program started in spring 2017, gurus have provided support and tutorials for their peers, primarily on WordPress and Adobe Creative Cloud, along with tips for effective audio and video recordings, photography, website development and more.

“A guru is usually someone—regardless of major or career path—who has a desire to help others,” M. Holden Andrews ’20, MDMS ’21 says. Andrews was one of two coordinators for the 2020-2021 academic year.

Emily Goodwin, Director of Instructional Design in the College’s Information Technology (IT) Center, started the gurus program as a way for more experienced students to help other students, as an increasing number of digital projects were being incorporated into classes at BC. Gurus are paid for their time, and, since fall 2019, one or two student coordinators have served as managers for the program. Coordinators have typically been gurus for one or two years and have often been graduate students in the Master of Arts in Digital Media Strategy (MDMS) program at BC.

The gurus have enjoyed increased visibility on campus since moving into the John Kenny Forrer Learning Commons. Their dedicated office on the first floor, next to the main circulation desk, is also adjacent to the Learning and Research Services Suite, where students can seek help on other class projects from the research librarians. The office is typically staffed by a coordinator, while the rest of the gurus usually station themselves throughout the Forrer Learning Commons for maximum accessibility. There are generally between three and seven gurus each semester, not counting the coordinators.

In addition to assisting students during their regular office hours, gurus go into classrooms (virtually and in person) to present how to use a program for a particular assignment, which is one of the primary ways they provide support to faculty. They also offer group help sessions on a particular topic or software several times a semester.

Gurus have a “passion for creating digital content, helping others create that content and helping their fellow students succeed,” says Dwayne Murrell ’20, MDMS ’21, the second program coordinator in 2020-21. Murrell says he became a guru because he wanted to expand his creative skillset and then pass those skills on to other students. The gurus are passionate about their work and eager to find ways to keep learning and growing in the role.

“The work doesn’t stop, but it’s always fun and always creative,” Andrews says.

Emily Helms ’16 was one of the student representatives who served on the Library Study Committee. She loved the experience of collaborating with faculty and staff on a vision for the new space. Today, she serves as Assistant Director of Admissions and transfer counselor in the College’s Office of Admissions. She says the Forrer Learning Commons—now a featured stop on prospective student tours—has made a “tremendous difference in the number of students who see Bridgewater College as a possible school choice than in the past.”

“For me, it’s being able to contribute to an idea that will last long beyond my time at Bridgewater,” Pearson says. “That’s a very satisfying moment as a professional librarian, to recognize that the work we’ve done here will benefit the College and the students for decades—that’s a rare opportunity. And that I had the opportunity to do that here at Bridgewater College is the highlight of my career.”

President Bushman envisions the fall of the 2021-22 academic year as a kind of second grand opening after COVID-19, a time when the Bridgewater College community can come together and truly make the space their own.

“The Learning Commons is not ‘finished.’ I don’t think it will ever be finished,” Rhea says. “We hope people will continue to think of new ways to use it.”

COMMUNITY SUPPORT

At $13.2 million, the Forrer Learning Commons is the largest donor-funded capital project on campus to date, both in terms of absolute dollars and in percentage of total cost. The transformative project attracted a breadth of contributions and broadened the College’s donor base, including 34 major gifts, 22 of which were from donors who made a gift at the major gift level ($25,000+) for the first time. In addition, two Virginia foundations, the Mary Morton Parsons Foundation and The Cabell Foundation, offered matching grants.

“In many ways, we were able to transform our relationships with alumni and friends around fundraising: We can do this. You can be a part of something bigger,” President Bushman says. “This was a really important proof of concept. Our alumni have been inspired that we can build something like this together.”

Bonnie Forrer Rhodes ’62 and her late husband, John H. Rhodes, are the primary benefactors of the Forrer Learning Commons, a tribute to Bonnie’s father, John Kenny Forrer, who had to leave Bridgewater College in 1928 after the sudden death of his father. Not only did Forrer, who went on to serve as Director and President of the Peoples Bank of Stuarts Draft, care for his family while working on their cattle farm, but he cared for his community as well. He was active in the Mount Vernon Church of the Brethren throughout his life and held formal positions as Deacon, Sunday School teacher and congressional delegate to the Brethren District Meetings. He counseled many members of the congregation on personal and family matters.

“My father was the person in the community who when someone needed help, they went to him,” Bonnie Rhodes says. “He took care of his family, extended family and the community. I really admired him for that.”

John and Bonnie Rhodes, too, have been dedicated to helping their communities, through charitable giving to a variety of causes. Bonnie Rhodes also currently serves as a member of the Bridgewater College Board of Trustees.

“I think giving makes life richer,” Rhodes says. “Anything that we can do to make things better in this world.”

She says Bridgewater College in particular holds special meaning for her and her late husband, a Pennsylvania State University graduate who as a young boy attended the Patton Masonic School for Boys, a small school located in Elizabethtown, Pa. It was John Rhodes’ beloved teacher, Mahlon Clark, who encouraged him to further his education at Penn State.

Bridgewater College mirrors that kind of close-knit community that fosters connections and encourages success.

“We thought the Learning Commons was a wonderful project,” Rhodes says. “This is a place that will really inspire students to study and do well. Any student who visits campus will say, ‘This is really special.’ I think it’s a wonderful thing for Bridgewater.”

Silva says it was almost surreal to step into the finished Learning Commons space and see the architectural designs brought to life. But what the designs couldn’t convey was the energy in the space as people engaged and collaborated in the way that was intended.

“That moment brought clarity to why we do the work that we do,” Silva says. “This project is meaningful for the College, it’s meaningful for the students. The investments from our donor partners are so impactful and will serve the institution for years to come.” She pauses and then adds, “How do you articulate the fulfillment of a dream?”

— By Jessica Luck